Emotions at Work

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Understand how emotions shape beliefs about the value of a job, company, or team.

- Understand Affective Events Theory (AET).

- Explain emotional labor and emotional intelligence.

- Understand the outcomes of stress.

- Understand individual differences in experienced stress.

Workplace communication doesn’t happen in a vacuum; it’s deeply influenced by how people feel. Emotions, whether sparked by a great team win or a stressful interaction, shape our attitudes about our jobs and colleagues. In this section, we’ll examine how emotions impact organizational communication. You’ll learn about Affective Events Theory, the concept of emotional labor, and what it means to have emotional intelligence. We’ll also explore how stress manifests at work, its impact on behavior, and why people respond differently. Understanding this emotional landscape is essential to building strong, supportive, and effective workplace relationships.

Affective Events Theory (AET)

Emotions shape an individual’s beliefs about the value of a job, a company, or a team. Emotions also affect behaviors at work. So, what is the connection between emotions, attitudes, and behaviors at work? This connection may be explained using Affective Events Theory (AET). Researchers Howard Weiss and Russell Cropanzano (1996) studied the effects of six primary emotions in the workplace: anger, fear, joy, love, sadness, and surprise. Their theory posits that specific events on the job elicit different emotions in various individuals. These emotions, in turn, inspire actions that can benefit or impede others at work (Fisher, 2002).

For example, imagine a coworker unexpectedly delivering your morning coffee to your desk. As a result of this pleasant, if unexpected experience, you may feel happy and surprised. If that coworker is your boss, you might feel proud as well. Studies have found that the positive feelings from work experience may inspire you to do something you hadn’t planned. For instance, you might volunteer to help a colleague on a project you weren’t planning to work on before. Your action would be an affect-driven behavior (Fisher, 2002). Alternatively, if your manager unfairly reprimanded you, the negative emotions you experience may cause you to withdraw from work or to act meanly toward a coworker. Over time, these tiny moments of emotion on the job can influence a person’s job satisfaction. Although company perks and promotions can contribute to a person’s happiness at work, satisfaction is not simply a result of this “outside-in” reward system. Job satisfaction in the AET model comes from the inside-in, combining an individual’s personality, small emotional experiences at work over time, beliefs, and affect-driven behaviors.

Jobs high in negative emotion can lead to frustration and burnout, an ongoing negative emotional state resulting from dissatisfaction (Lee & Ashforth, 1996; Maslach, 1982; Maslach & Jackson, 1981). Depression, anxiety, anger, physical illness, increased drug and alcohol use, and insomnia can result from frustration and burnout, with frustration being somewhat more active and burnout more passive. The effects of both conditions can impact coworkers, customers, and clients as anger boils over and is expressed in one’s interactions with others (Lewandowski, 2003).

Emotional Labor

Negative emotions are prevalent among workers in the service industry. Individuals who work in manufacturing rarely meet their customers face-to-face. If they’re in a bad mood, the customer would not know. Service jobs are just the opposite. Part of a service employee’s job is to appear a certain way in the eyes of the public. Individuals in service industries are professional helpers. As such, they are expected always to be upbeat, friendly, and polite, which can be exhausting in the long run. Humans are emotional creatures by nature. In a day, we experience a wide range of emotions. Think about your day thus far. Can you identify times when you were happy dealing with others and wanted to be left alone? Now imagine trying to hide all the emotions you’ve felt today for 8 hours or more at work. That’s what cashiers, school teachers, massage therapists, firefighters, and librarians, among other professionals, are asked to do. Individuals may be sad, angry, or fearful, but their job title often takes precedence over their identity at work. The result is a persona, a professional role that involves acting out feelings that may not be real as part of their job.

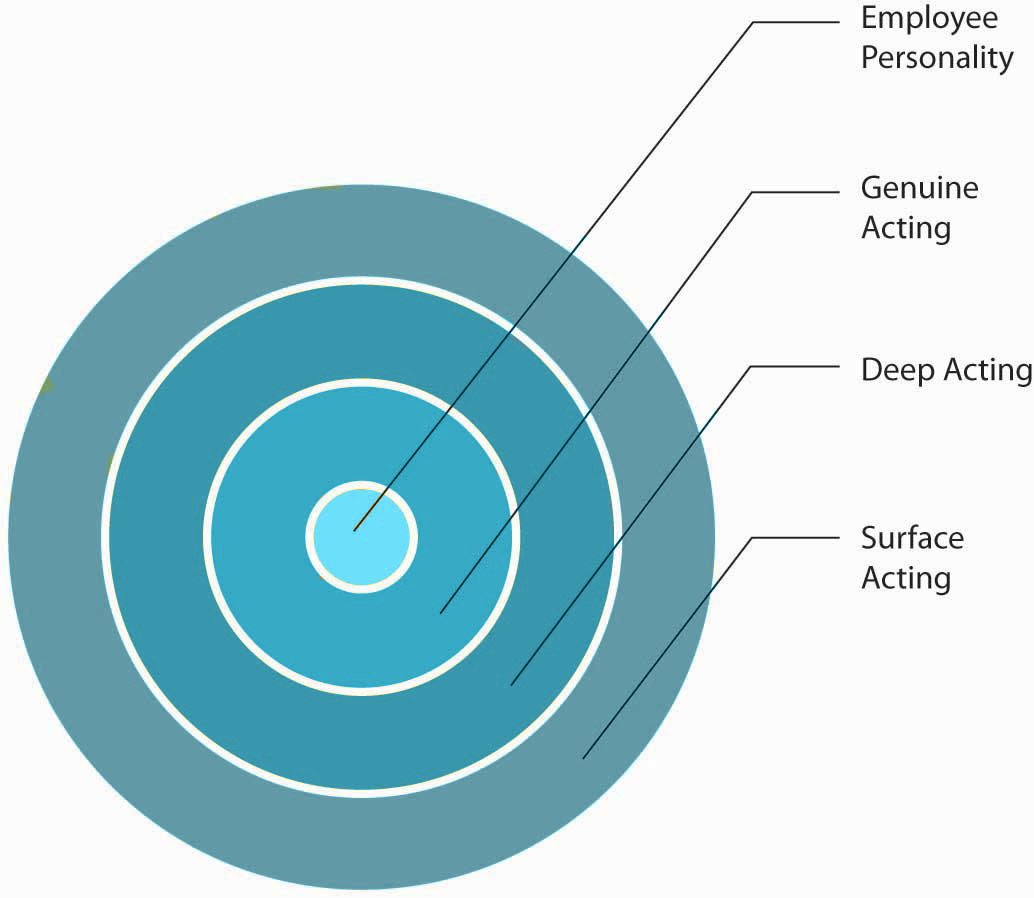

Three primary levels of emotional labor have been identified (Hochschild, 1983).

- Surface acting requires an individual to exhibit physical signs, such as smiling, that reflect emotions customers want to experience. For example, a children’s hairdresser cutting the hair of a crying toddler may smile and act sympathetic without actually feeling so. In this case, the person is engaged in surface acting.

- Deep acting takes surface acting one step further. This time, instead of faking an emotion that a customer may want to see, an employee will actively try to experience the feeling they are displaying. This genuine attempt at empathy helps align the emotions one is experiencing with those one is displaying. The children’s hairdresser may empathize with the toddler by imagining how stressful it must be for one so young to be confined to a chair and in an unfamiliar environment. The hairdresser may genuinely begin to feel sad for the child.

- Genuine acting occurs when individuals are asked to display emotions aligned with their own. If a job requires genuine acting, less emotional labor is needed because the actions are consistent with authentic feelings.

When it comes to acting, the closer your actions are to the middle of the circle, the less emotional labor your job demands. The further away, the more emotional labor the job demands. Research indicates that surface acting is associated with higher stress levels and fewer experienced positive emotions, whereas deep acting may result in lower stress (Beal et al., 2006; Grandey, 2003). Emotional labor is widespread in service industries characterized by relatively low pay, which creates the added potential for stress and feelings of being mistreated (Glomb et al., 2004; Rupp & Sharmin, 2006).

In a study of 285 hotel employees, researchers found that emotional labor was vital because many employee-customer interactions involved individuals dealing with emotionally charged issues (Chu, 2002). Emotional laborers are required to display specific emotions as part of their jobs. Sometimes, these are emotions that the worker already feels. In that case, the strain of the emotional labor is minimal. For example, a funeral director is expected to sympathize with a family’s loss. In the case of a family member suffering an untimely death, this emotion may be genuine. But for people whose jobs require them to be professionally polite and cheerful, such as flight attendants, or to be serious and authoritative, such as police officers, the work of wearing one’s “game face” can have effects that outlast the working day. Taking breaks can help actors cope more effectively with this (Beal et al., 2008). Additionally, researchers have found that greater autonomy is associated with lower strain for service workers in the United States and France (Grandey et al., 2005).

Cognitive dissonance is a term that refers to a mismatch among emotions, attitudes, beliefs, and behavior, for example, believing that you should always be polite to a customer regardless of personal feelings, yet having just been rude to one. You’ll experience discomfort or stress unless you can alleviate the dissonance. You can reduce the personal conflict by changing your behavior (trying harder to act polite), changing your belief (maybe it’s OK to be a little less polite sometimes), or by adding a new fact that changes the importance of the previous facts (such as you will otherwise be laid off the next day). Although acting positive can make a person feel positive, emotional labor that involves a significant degree of emotional or cognitive dissonance can be grueling, sometimes leading to adverse health effects (Zapf, 2006).

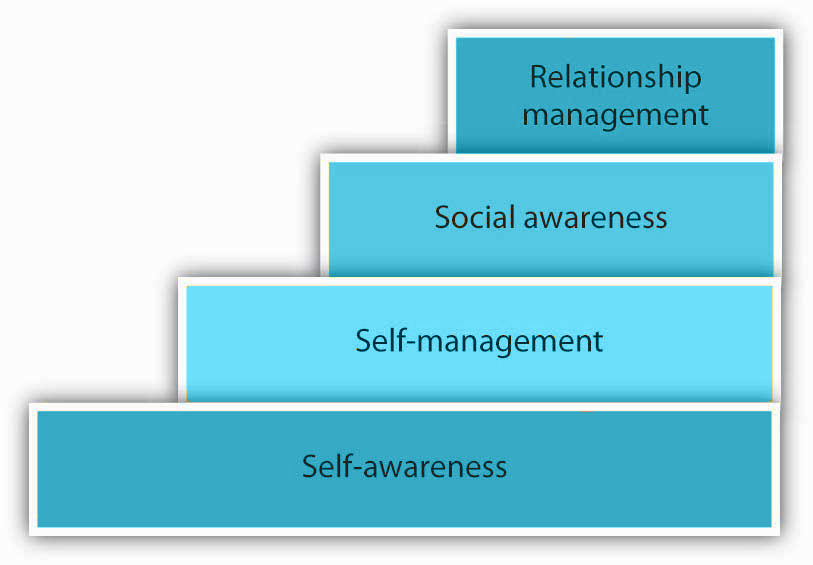

Emotional Intelligence

One way to manage the effects of emotional labor is to increase your awareness of the gaps between real emotions and emotions that your professional persona requires. “What am I feeling? And what do others feel?” These questions form the heart of emotional intelligence. Emotional intelligence examines how people can understand each other more completely by increasing awareness of their own and others’ emotions (Carmeli, 2003). Four building blocks are involved in developing a high level of emotional intelligence. Self-awareness exists when you can accurately perceive, evaluate, and display appropriate emotions. Self-management exists when you can positively direct your feelings when needed. Social awareness exists when you can understand how others feel. Relationship management exists when you can help others manage their emotions and establish supportive relationships with others (Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002; Weisinger, 1998).

In the workplace, emotional intelligence can be leveraged to foster harmonious teams by harnessing the talents of every member. To accomplish this, colleagues well-versed in emotional intelligence can look for opportunities to motivate themselves and inspire others to work together (Goleman, 1995). Chief among the emotions that helped create a successful team, Goleman learned, was empathy, the ability to put oneself in another’s shoes, whether that individual has achieved a major triumph or fallen short of personal goals (Goleman, 1998). Those high in emotional intelligence have been found to have higher self-efficacy in coping with adversity, perceive situations as challenges rather than threats, and exhibit higher life satisfaction, all of which can help lower stress levels (Law et al., 2004; Mikolajczak & Luminet, 2008).

Managing Stress at Work

Gravity. Mass. Magnetism. These words come from the physical sciences. And so does the term stress. In its original form, stress relates to the force applied to a given area. A steel bar stacked with bricks is being stressed in ways that can be measured using mathematical formulas. In human terms, psychiatrist Peter Panzarino notes, “Stress is simply a fact of nature, forces from the outside world affecting the individual” (Panzarino, 2008). Modern life’s professional, personal, and environmental pressures exert their forces on us every day. Some of these pressures are good. Others can wear us down over time. Psychologists define stress as the body’s reaction to a change that requires a physical, mental, or emotional adjustment or response (Dyer, 2006). Stress is an inevitable feature of life. It is the force that gets us out of bed in the morning, motivates us at the gym, and inspires us to work.

As you will see in the sections below, stress is a given factor in our lives. We may not be able to avoid stress altogether, but we can change how we respond to stress, which is a significant benefit. Our ability to recognize, manage, and effectively respond to stress can transform an emotional or physical issue into a valuable resource. Researchers use polling to measure the effects of stress at work. The results have been eye-opening. According to a 2001 Gallup poll, 80% of American workers report feeling workplace stress at least some of the time (Kersten, 2002). Another survey found that 65% of workers reported job stress as an issue for them, and almost as many employees ended the day exhibiting physical effects of stress, including neck pain, aching muscles, and insomnia. Many individuals are stressed at work.

The Stress Process

Our lower brains control basic human functions, such as breathing, blinking, heartbeat, digestion, and other unconscious actions. Outside this portion of the brain lies the semiconscious limbic system, which plays a significant role in human emotions. Within this system is an area known as the amygdala. The amygdala is responsible for stimulating fear responses, among other things. Unfortunately, the amygdala cannot distinguish between meeting a 10:00 a.m. marketing deadline and escaping a burning building. Human brains respond to outside threats to our safety with a message to our bodies to engage in a “fight-or-flight” response (Cannon, 1915). Our bodies prepare for these scenarios with an increased heart rate, shallow breathing, and wide-eyed focus. Even digestion and other functions are stopped in preparation for the fight-or-flight response. While these traits allowed our ancestors to flee the scene of their impending doom or engage in a physical battle for survival, most crises at work are not as dramatic as this.

Hans Selye, one of the founders of the American Institute of Stress, spent his life examining the human body’s response to stress. As an endocrinologist who studied the effects of adrenaline and other hormones on the body, Selye believed that unmanaged stress could create physical diseases such as ulcers and high blood pressure, and psychological illnesses such as depression. He hypothesized that stress played a general role in disease by exhausting the body’s immune system and termed this the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) (Selye, 1956; Selye, 1976).

In the alarm phase of stress, an external stressor jolts the individual, prompting them to take action. It may help to think of this as the fight-or-flight moment in the individual’s experience. If the response is sufficient, the body will return to its resting state after successfully dealing with the source of stress. During the resistance phase, the body begins to release cortisol and draws on its reserves of fats and sugars to adjust to the stress demands. This reaction works well for short periods, but it is only a temporary fix. Individuals forced to endure the stress of cold and hunger may find a way to adjust to lower temperatures and less food. While it is possible for the body to “adapt” to such stresses, the situation cannot continue. The body is drawing on its reserves, like a hospital using backup generators after a power failure. It can continue functioning by shutting down unnecessary items, such as large overhead lights, elevators, televisions, and most computers, but it cannot remain in that state forever.

In the exhaustion phase, the body has depleted its stores of sugars and fats, and the prolonged release of cortisol has caused the stressor to significantly weaken the individual. Disease results from the body’s weakened state, leading to death in the most extreme cases. This eventual depletion is why we’re more likely to reach for foods rich in fat or sugar, caffeine, or other quick fixes that provide us with energy when we’re stressed. Selye referred to stress that led to disease as distress and anxiety that was enjoyable or healing as eustress.

Workplace Stressors

Stressors are events or contexts that cause stress by elevating adrenaline levels and forcing a physical or mental response. The key to remembering stressors is that they aren’t necessarily bad. The saying “the straw that broke the camel’s back” applies to stressors. Having a few stressors in our lives may not be a problem, but because stress is cumulative, having multiple stressors day after day can cause a buildup that becomes a significant issue. The American Psychological Association surveys American adults about their stresses annually. Money, work, and housing are among the top stressors (American Psychological Association, 2007). However, in essence, we could say that all three problems ultimately stem from the workplace. The amount we earn determines the kind of housing we can afford, and when job security is questionable, our home life is also generally affected. Understanding what can potentially cause stress can help avoid negative consequences. We will now examine the major stressors in the workplace. Role demands are a significant category of workplace stressors. In other words, some jobs and work contexts are more potentially stressful than others.

Role Demands

Role ambiguity refers to vagueness about what our responsibilities are. If you have started a new job and felt unclear about what you were expected to do, you have experienced role ambiguity. High role ambiguity is related to higher emotional exhaustion, more thoughts of leaving an organization, and lowered job attitudes and performance (Fisher & Gittelson, 1983; Jackson & Shuler, 1985; Örtqvist & Wincent, 2006). Role conflict refers to facing contradictory demands at work. For example, your manager may want you to increase customer satisfaction and cut costs, while you feel that satisfying customers inevitably increases costs. In this case, you are experiencing role conflict because satisfying one demand is unlikely to meet the other. Role overload is insufficient time and resources to complete a job. When an organization downsizes, the remaining employees must take on the tasks previously performed by the laid-off workers, which often leads to role overload. Like role ambiguity, role conflict and role overload have been shown to impact performance and lower job attitudes negatively; however, research indicates that role ambiguity is the strongest predictor of poor performance (Gilboa et al., 2008; Tubre & Collins, 2000). Research on new employees also indicates that role ambiguity is a significant factor in their adjustment, and that when role ambiguity is high, new employees struggle to integrate into the new organization (Bauer et al., 2007).

Information Overload

Messages reach us in countless ways every day. Some are societal advertisements that we may encounter throughout our day. Others include professional emails, memos, voicemails, and conversations with our colleagues. Others are personal messages and conversations from our loved ones and friends. Add these together, and it’s easy to see how we may receive more information than we can. This state of imbalance is known as information overload, which can be defined as “occurring when the information processing demands on an individual’s time to perform interactions and internal calculations exceed the supply or capacity of time available for such processing” (Schick, Gordon, & Haka, 1990). Role overload has become much more salient due to the ease with which we can access abundant information from Web search engines and the numerous emails and text messages we receive daily (Dawley & Anthony, 2003).[1] Research indicates that working in a fragmented manner significantly impacts efficiency, creativity, and mental acuity (Overholt, 2001).

Top 10 Stressful Jobs

As you can see, some of these jobs are stressful due to high emotional labor (customer service), physical demands (mining), time pressures (journalist), or all three (police officer):

- Inner city high school teacher

- Police officer

- Miner

- Air traffic controller

- Medical intern

- Stockbroker

- Journalist

- Customer service or complaint worker

- Secretary

- Waiter

Source: Tolison, B. (2008, April 7). Top ten most stressful jobs. Health. Retrieved January 28, 2009, from the WCTV News Website: www.wctv.tv/news/headlines/17373899.html.

Work–Family Conflict

Work–family conflict occurs when the demands from work and family negatively affect one another (Netemeyer, Boles, & McMurrian, 1996). Specifically, work and family demands may be incompatible, such that work interferes with family life and family demands interfere with work life. This stressor has steadily increased in prevalence as work has become more demanding and technology has enabled employees to work from home, remaining connected to their jobs around the clock. A recent census revealed that 28% of the American workforce works more than 40 hours per week, resulting in an unavoidable spillover from work to family life (U.S. Census Bureau, 2004). Moreover, the fact that more households have dual-earning families, in which both adults work, means that household and childcare duties are no longer the sole responsibility of a stay-at-home parent. This trend only compounds stress from the workplace by leading to the spillover of family responsibilities (such as a sick child or elderly parent) to work life. Research shows that individuals who have stress in one area of their life tend to have greater stress in other parts of their lives, which can create a situation of escalating stressors (Allen et al., 2000; Ford, Heinen, & Langkamer, 2007; Frone, Russell, & Cooper, 1992; Hammer, Bauer, & Grandey, 2003).

Work–family conflict is related to lower job and life satisfaction. Interestingly, it seems that work–family conflict is slightly more problematic for women than men (Kossek & Ozeki, 1998). Organizations that help their employees achieve a greater work–life balance are perceived as more attractive than those that do not (Barnett & Hall, 2001; Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). Organizations can help employees maintain a work–life balance by implementing organizational practices such as flexibility in scheduling and individual practices, including having supervisors who are supportive and considerate of employees’ family life (Thomas & Ganster, 1995).

Life Changes

Stress can result from positive and negative life changes. The Holmes-Rahe scale ascribes different stress values to life events ranging from the death of one’s spouse to receiving a ticket for a minor traffic violation. The values are based on incidences of illness and death 12 months after each event. On the Holmes-Rahe scale, the death of a spouse receives a stress rating of 100, getting married is seen as a midway stressful event, with a rating of 50, and losing one’s job is rated as 47. These numbers are relative values that enable us to understand the impact of various life events on our stress levels and their effect on our health and well-being (Fontana, 1989). Again, because stressors are cumulative, higher scores on the stress inventory mean you are more prone to suffering negative consequences of stress than someone with a lower score.

Exercises

Read each of the events listed below. Give yourself the number of points next to any event in your life in the last 2 years. There are no right or wrong answers. The aim is to identify which of these events you have experienced.

| Life event | Stress points | Life event | Stress points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death of spouse | 100 | Foreclosure of a mortgage or a loan | 30 |

| Divorce | 73 | Change in responsibilities at work | 29 |

| Marital separation | 65 | Son or daughter leaving home | 29 |

| Jail term | 63 | Trouble with in-laws | 29 |

| Death of a close family member | 63 | Outstanding personal achievement | 28 |

| Personal injury or illness | 53 | Begin or end school | 26 |

| Marriage | 50 | Change in living location/condition | 25 |

| Fired or laid off at work | 47 | Trouble with the supervisor | 23 |

| Marital reconciliation | 45 | Change in work hours or conditions | 20 |

| Retirement | 45 | Change in schools | 20 |

| Pregnancy | 40 | Change in social activities | 18 |

| Change in financial state | 38 | Change in eating habits | 15 |

| Death of a close friend | 37 | Vacation | 13 |

| Change to a different line of work | 36 | Minor violations of the law | 11 |

Scoring:

- If you scored fewer than 150 stress points, you have a 30% chance of developing a stress-related illness shortly.

- If you scored between 150 and 299 stress points, you have a 50% chance of developing a stress-related illness shortly.

- If you scored over 300 stress points, you have an 80% chance of developing a stress-related illness shortly.

The happy events in this list, such as getting married or achieving an outstanding personal goal, illustrate how eustress, or “good stress,” can also tax the body as much as the stressors that constitute the traditionally negative distress category. (The prefix eu- in the word eustress means “good” or “well,” much like the eu- in euphoria.) Stressors can also occur in trends. For example, in 2007, nearly 1.3 million U.S. housing properties were subject to foreclosure, up 79% from 2006.

Source: Adapted from Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11, 213–218.

Downsizing

A study commissioned by the U.S. Department of Labor, examining over 3,600 companies from 1980 to 1994, found that manufacturing firms accounted for the most significant incidence of major downsizings. The average percentage of firms by industry that downsized more than 5% of their workforce across the 15-year study period was manufacturing (25%), retail (17%), and service (15%). 59% of the companies studied fired at least 5% of their employees at least once during the 15 years, and 33% downsized more than 15% of their workforce at least once. Furthermore, during the recessions of 1985-1986 and 1990-1991, more than 25% of all firms, regardless of size, reduced their workforce by more than 5% (Slocum et al., 1999). In the United States, major layoffs in many sectors in 2008 and 2009 were stressful even for those who retained their jobs.

The loss of a job can be a particularly stressful event, as evidenced by its high score on the life stressors scale. It can also lead to other stressful events, such as financial difficulties, which can contribute to a person’s overall stress level. Research shows that downsizing and job insecurity (worrying about downsizing) are related to greater stress, alcohol use, and lower performance and creativity (Moore, Grunberg, & Greenberg, 2004; Probst et al., 2007; Sikora et al., 2008). For example, a study of over 1,200 Finnish workers found that past downsizing or expectations of future downsizing were associated with greater psychological strain and absenteeism (Kalimo, Taris, & Schaufeli, 2003). In another study on creativity and downsizing, researchers found that creativity and most aspects of the perceived work environment that support creativity declined significantly during the downsizing process (Amabile & Conti, 1999). Those who experience layoffs but have self-integrity affirmed through other means are less susceptible to adverse outcomes (Wisenfeld et al., 2001).

Outcomes of Stress

The outcomes of stress are categorized into physiological, psychological, and work outcomes.

Physiological

Stress manifests internally as nervousness, tension, headaches, anger, irritability, and fatigue. Stress can also have outward manifestations. Dr. Dean Ornish, author of Stress, Diet, and Your Heart, states that stress is related to aging (Ornish, 1984). Chronic stress causes the body to secrete hormones, such as cortisol, which can blemish our complexion and contribute to the development of wrinkles. Harvard psychologist Ted Grossbart, author of Skin Deep, says, “Tens of millions of Americans suffer from skin diseases that flare up only when they’re upset” (Grossbart, 1992). These skin problems include itching, profuse sweating, warts, hives, acne, and psoriasis. For example, Roger Smith, the former CEO of General Motors Corporation, was featured in a Fortune article that began, “His normally ruddy face is covered with a red rash, a painless but disfiguring problem which Smith says his doctor attributes 99% to stress” (Taylor, 1987).

The human body responds to external stimuli by pumping more blood through its system, breathing more deeply, and gazing wide-eyed at the world. To accomplish this feat, our bodies shut down our immune systems. From a biological point of view, it’s a smart strategic move—but only in the short term. The idea can be seen as your body’s way of trying to escape an imminent threat, so there is still some kind of body around to get sick later. However, in the long term, a body under constant stress can excessively suppress its immune system, leading to health problems such as high blood pressure, ulcers, and increased susceptibility to illnesses like the common cold. The link between heart attacks and stress, while easy to assume, has been harder to prove. The American Heart Association notes that research has yet to establish a definitive link between the two. Regardless, it is clear that individuals under stress engage in behaviors that can lead to heart disease, such as eating fatty foods, smoking, or failing to exercise.

Psychological

Depression and anxiety are two psychological outcomes of unchecked stress, which are as dangerous to our mental health and welfare as heart disease, high blood pressure, and strokes. The Harris poll found that 11% of respondents said a sense of depression accompanied their stress. “Persistent or chronic stress has the potential to put vulnerable individuals at a substantially increased risk of depression, anxiety, and many other emotional difficulties,” notes Mayo Clinic psychiatrist Daniel Hall-Flavin. Scientists have pointed out that changes in brain function—particularly in the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland—may play a significant role in stress-induced emotional problems (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2008).

Work Outcomes

Stress is associated with worse job attitudes, higher turnover, and decreased job performance, encompassing both in-role performance and organizational citizenship behaviors (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2008; Gilboa et al., 2008; Podsakoff et al., 2007). Research also indicates that individuals experiencing stress tend to have lower organizational commitment compared to those who are less stressed (Cropanzano, Rupp, & Byrne, 2003). Interestingly, job challenges are related to higher performance, with some individuals rising to the challenge (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & MacKenzie, 2007). The key is to keep challenges in the optimal zone for stress—the activation stage—and avoid exhaustion (Quick et al., 1997).

Individual Differences in Experienced Stress

How we handle stress varies by individual, and part of that issue concerns our personality type. Type A personalities, as defined by the Jenkins Activity Survey (Jenkins, Zyzanski, & Rosenman, 1979), display high levels of speed/impatience, job involvement, and hard-driving competitiveness. Suppose you think back to Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome, in which unchecked stress can lead to illness over time. In that case, it’s easy to see how a Type A person’s fast-paced, adrenaline-pumping lifestyle can lead to increased stress, and research supports this view (Spector & O’Connell, 1994). Studies show that the hostility and hyper-reactive portion of the Type A personality is a significant concern in terms of stress and adverse organizational outcomes (Ganster, 1986).

Type B personalities, by contrast, are calmer by nature. They think through situations rather than reacting emotionally, which reduces their fight-or-flight response and stress levels. Our personalities are the outcome of our life experiences and, to some degree, our genetics. Some researchers believe that mothers who experience a great deal of stress during pregnancy introduce their unborn babies to high levels of the stress-related hormone cortisol in utero, predisposing their babies to a stressful life from birth (BBC News, 2007). Men and women also handle stress differently. Researchers at Yale University discovered that estrogen may heighten women’s response to stress and their tendency to depression as a result (Weaver, 2004). Still, others believe women’s stronger social networks allow them to process stress more effectively than men. So while women may become depressed more often than men, women may also have better tools for countering emotion-related stress than their male counterparts.

As we all know, stress can build up. Advice often given is to “let it all out” with something like a cathartic “good cry.” However, research suggests that crying may not be as beneficial as the adage implies. In reviewing scientific studies on crying and health, Ad Vingerhoets and Jan Scheirs found that the studies “yielded little evidence supporting the hypothesis that shedding tears improves mood or health directly, be it in the short or the long run.” Another study found that venting increased the adverse effects of negative emotion (Brown, Westbrook, & Challagalla, 2005). Instead, laughter may be the better remedy. Crying may intensify negative feelings because it serves as a social signal to others and yourself. “You might think, ‘I didn’t think it was bothering me that much, but look at how I’m crying—I must be upset,’” says Susan Labott of the University of Toledo. The crying may intensify the feelings. Labott and Randall Martin of Northern Illinois University at DeKalb surveyed 715 men and women. They found that at comparable stress levels, criers were more depressed, anxious, hostile, and tired than those who wept less. Those who used humor were the most successful at combating stress. So, if you’re looking for a cathartic release, opt for humor instead: Try to find something funny in your stressful predicament.

Key Takeaways

- Emotions affect attitudes and behaviours at work.

- Affective Events Theory can help explain these relationships.

- Emotional labor is higher when one is asked to act in a way that is inconsistent with their personal feelings.

- Surface acting requires a high level of emotional labor.

- Emotional intelligence refers to understanding how others are reacting to our emotions.

- Stress is prevalent in today’s workplaces. If it persists for too long, the general adaptation syndrome consists of alarm, resistance, and eventually exhaustion.

- Time pressure is a significant stressor. Stress outcomes encompass psychological and physiological issues, as well as work-related consequences. Individuals with Type B personalities tend to be less prone to stress, and those with social support often experience less stress.

References

This section is adapted from:

Allen, T. D., Herst, D. E. L., Bruck, C. S., & Sutton, M. (2000). Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 278–308.

Amabile, T. M., & Conti, R. (1999). Changes in the work environment for creativity during downsizing. Academy of Management Journal, 42, 630–640.

American Psychological Association. (2007, October 24). Stress a major health problem in the U.S., warns APA. Retrieved May 21, 2008, from the American Psychological Association Web site: www.apa.org/releases/stressproblem.html.

8.5 Emotions at Work in NSCC Organizational Behaviour by NSCC is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Barnett, R. C., & Hall, D. T. (2001). How to use reduced hours to win the war for talent. Organizational Dynamics, 29, 192–210.

Bauer, T. N., Bodner, T., Erdogan, B., Truxillo, D. M., & Tucker, J. S. (2007). Newcomer adjustment during organizational socialization: A meta-analytic review of antecedents, outcomes, and methods. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 707–721.

BBC News. (2007, January 26). Stress “harms brain in the womb.” Retrieved May 23, 2008, from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/6298909.stm.

Beal, D. J., Green, S. G., & Weiss, H. (2008). Making the break count: An episodic examination of recovery activities, emotional experiences, and positive affective displays. Academy of Management Journal, 51, 131–146.

Beal, D. J., Trougakos, J. P., Weiss, H. M., & Green, S. G. (2006). Episodic processes in emotional labor: Perceptions of affective delivery and regulation strategies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1053–1065.

Brown, S. P., Westbrook, R. A., & Challagalla, G. (2005). Good cope, bad cope: Adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies following a critical negative work event. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 792–798.

Cannon, W. (1915). Bodily changes in pain, hunger, fear and rage: An account of recent researches into the function of emotional excitement. New York: D. Appleton.

Carmeli, A. (2003). The relationship between emotional intelligence and work attitudes, behaviour and outcomes: An examination among senior managers. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18, 788–813.

Chu, K. (2002). The effects of emotional labor on employee work outcomes [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Cropanzano, R., Rupp, D. E., & Byrne, Z. S. (2003). The relationship of emotional exhaustion to work attitudes, job performance, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 160–169.Elfenbein, H. A., & Ambady, N. (2002). Is there an in-group advantage in emotion recognition? Psychological Bulletin, 128, 243–249.

Dawley, D. D., & Anthony, W. P. (2003). User perceptions of e-mail at work. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 17, 170–200.

Dyer, K. A. (2006). Definition of stress. Retrieved May 21, 2008, from About.com: http://dying.about.com/od/glossary/g/stress_distress.htm.

Elfenbein, H. A., & Ambady, N. (2002). Predicting workplace outcomes from the ability to eavesdrop on feelings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 963–971.

Fisher, C. D., & Gittelson, R. (1983). A meta-analysis of the correlates of role conflict and role ambiguity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 68, 320–333.Fisher, C. D. (2002). Real-time affect at work: A neglected phenomenon in organizational behaviour. Australian Journal of Management, 27, 1–10.

Fontana, D. (1989). Managing stress. Published by the British Psychology Society and Routledge.Glomb, T. M., Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., & Rotundo, M. (2004). Emotional labor demands and compensating wage differentials. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 700–714.

Ford, M. T., Heinen, B. A., & Langkamer, K. L. (2007). Work and family satisfaction and conflict: A meta-analysis of cross-domain relations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 57–80.

Frone, M. R., Russell, R., & Cooper, M. L. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work–family conflict: Testing a model of the work–family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 65–78.

Ganster, D. C. (1986). Type A behavior and occupational stress. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 8, 61–84.

Gilboa, S., Shirom, A., Fried, Y., & Cooper, C. (2008). A meta-analysis of work demand stressors and job performance: Examining main and moderating effects. Personnel Psychology, 61, 227–271.

Grandey, A. (2000). Emotional regulations in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 95–110.

Grandey, A. A. (2003). When “the show must go on”: Surface acting and deep acting as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peer-rated service delivery. Academy of Management Journal, 46, 86–96.

Grandey, A. A., Fisk, G. M., & Steiner, D. D. (2005). Must “service with a smile” be stressful? The moderating role of personal control for American and French employees. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 893–904.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work–family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31, 72–92.

Grossbart, T. (1992). Skin deep. New Mexico: Health Press.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. Bantam Books.

Goleman, D. (1998). Working with emotional intelligence. Bantam Books.

Hammer, L. B., Bauer, T. N., & Grandey, A. A. (2003). Work–family conflict and work–related withdrawal behaviors. Journal of Business & Psychology, 17, 419–436.

Hochschild, A. (1983). The managed heart. University of California Press.

Jackson, S. E., & Shuler, R. S. (1985). A meta-analysis and conceptual critique of research on role ambiguity and role conflict in work settings. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 36, 16–78.

Jenkins, C. D., Zyzanski, S., & Rosenman, R. (1979). Jenkins activity survey manual. New York: Psychological Corporation.

Kalimo, R., Taris, T. W., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2003). The effects of past and anticipated future downsizing on survivor well-being: An Equity perspective. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 8, 91–109.

Kersten, D. (2002, November 12). Get a grip on job stress. USA Today. Retrieved May 21, 2008, from http://www.usatoday.com/money/jobcenter/workplace/stress management/2002-11-12-job-stress_x.htm.

Kossek, E. E., & Ozeki, C. (1998). Work–family conflict, policies, and the job–life satisfaction relationship: A review and directions for organizational behavior–human resources research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 139–149.

Law, K. S., Wong, C., & Song, L. J. (2004). The construct and criterion validity of emotional intelligence and its potential utility for management studies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 483–496.

Lee, R. T., & Ashforth, B. E. (1996). A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of three dimensions of job burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 123–133.

Lewandowski, C. A. (2003). Organizational factors contributing to worker frustration: The precursor to burnout. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 30, 175–185.

Maslach, C. (1982). Burnout: The cost of caring. Prentice Hall.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior, 2, 99–113.

Mayo Clinic Staff. (2008, February 26). Chronic stress: Can it cause depression? Retrieved May 23, 2008, from the Mayo Clinic Web site: www.mayoclinic.com/health/stress/AN01286.

Mikolajczak, M., & Luminet, O. (2008). Trait emotional intelligence and the cognitive appraisal of stressful events: An exploratory study. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 1445–1453.

Moore, S., Grunberg, L., & Greenberg, E. (2004). Repeated downsizing contact: The effects of similar and dissimilar layoff experiences on work and well-being outcomes. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 9, 247–257.

Netemeyer, R. G., Boles, J. S., & McMurrian, R. (1996). Development and validation of work–family conflict and family–work conflict scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 400–410.

Ornish, D. (1984). Stress, diet and your heart. New York: Signet.

Örtqvist, D., & Wincent, J. (2006). Prominent consequences of role stress: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of Stress Management, 13, 399–422.

Overholt, A. (2001, February). Intel’s got (too much) mail. Fast Company. Retrieved May 22, 2008, from www.fastcompany.com/online/44/intel.html and http://blogs.intel.com/it/2006/10/information_overload.php.

Panzarino, P. (2008, February 15). Stress. Retrieved from Medicinenet.com. Retrieved May 21, 2008, from http://www.medicinenet.com/stress/article.htm.

Podsakoff, N. P., LePine, J. A., & LePine, M. A. (2007). Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 438–454.

Probst, T. M., Stewart, S. M., Gruys, M. L., & Tierney, B. W. (2007). Productivity, counterproductivity and creativity: The ups and downs of job insecurity. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 80, 479–497.

Quick, J. C., Quick, J. D., Nelson, D. L., & Hurrell, J. J. (1997). Preventative stress management in organizations. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Rupp, D. E., & Sharmin, S. (2006). When customers lash out: The effects of customer interactional injustice on emotional labor and the mediating role of discrete emotions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 971–978.

Schick, A. G., Gordon, L. A., & Haka, S. (1990). Information overload: A temporal approach. Accounting, organizations, and society, 15, 199–220.

Selye, H. (1946). The general adaptation syndrome and the diseases of adaptation. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology, 6, 117.

Selye, H. (1976). Stress of life (Rev. ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Sikora, P., Moore, S., Greenberg, E., & Grunberg, L. (2008). Downsizing and alcohol use: A cross-lagged longitudinal examination of the spillover hypothesis. Work & Stress, 22, 51–68.

Slocum, J. W., Morris, J. R., Cascio, W. F., & Young, C. E. (1999). Downsizing after all these years: Questions and answers about who did it, how many did it, and who benefited from it. Organizational Dynamics, 27, 78–88.

Spector, P. E., & O’Connell, B. J. (1994). The contribution of personality traits, negative affectivity, locus of control and Type A to the subsequent reports of job stressors and job strains. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 67, 1–11.

Taylor, A. (1987, August 3). The biggest bosses. Fortune. Retrieved May 23, 2008, from http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/1987/08/03/69388/index.htm.

Thomas, L. T., & Ganster, D. C. (1995). Impact of family-supportive work variables on work–family conflict and strain: A control perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80, 6–15.

Tubre, T. C., & Collins, J. M. (2000). Jackson and Schuler (1985) Revisited: A meta-analysis of the relationships between role ambiguity, role conflict, and performance. Journal of Management, 26, 155–169.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2004). Labor Day 2004. Retrieved May 22, 2008, from the U.S. Census Bureau Web site: www.census.gov/press-release/…ns/002264.html.

Weisinger, H. (1998). Emotional intelligence at work. Jossey-Bass.

Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 18, 1–74.

Weaver, J. (2004, January 21). Estrogen makes the brain more vulnerable to stress. Yale University Medical News. Retrieved May 23, 2008, from http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2004-01/yu-emt012104.php.

Wiesenfeld, B. M., Brockner, J., Petzall, B., Wolf, R., & Bailey, J. (2001). Stress and coping among layoff survivors: A self-affirmation analysis. Anxiety, Stress & Coping: An International Journal, 14, 15–34.

Zapf, D. (2006). On the positive and negative effects of emotion work in organizations. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 15, 1–28.

Attribution

Psychology, Communication, and the Canadian Workplace Copyright © 2022 by Laura Westmaas, BA, MSc is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Figure 4.3 According to Affective Events Theory, six emotions are affected by events at work. Image: University of Minnesota and NSCC, NSCC Organizational Behaviour. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Color altered from original.

Figures 4.4 & 4.5 Image: University of Minnesota and NSCC, NSCC Organizational Behaviour. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Color altered from original.

This page, 7.2: What Is Stress?, is shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Anonymous.

a psychological model that explains how workplace events can trigger emotional reactions in employees, which in turn influence their job satisfaction, performance, and other work-related attitudes and behaviors.

a term that refers to a mismatch among emotions, attitudes, beliefs, and behavior, for example, believing that you should always be polite to a customer regardless of personal feelings, yet having just been rude to one.

examines how people can understand each other more completely by increasing awareness of their own and others’ emotions.

exists when you can accurately perceive, evaluate, and display appropriate emotions.

exists when you can positively direct your feelings when needed.

exists when you can understand how others feel.

exists when you can help others manage their emotions and establish supportive relationships with others.

the ability to put oneself in another’s shoes, whether that individual has achieved a major triumph or fallen short of personal goals.

relates to the force applied to a given area.

is responsible for stimulating fear responses, among other things.

events or contexts that cause stress by elevating adrenaline levels and forcing a physical or mental response.

refers to vagueness about what our responsibilities are.

is related to higher emotional exhaustion, more thoughts of leaving an organization, and lowered job attitudes and performance.

refers to facing contradictory demands at work.

insufficient time and resources to complete a job.

occurs when the demands from work and family negatively affect one another.

categorized into physiological, psychological, and work outcomes.

display high levels of speed/impatience, job involvement, and hard-driving competitiveness.

Calmer by nature. They think through situations rather than reacting emotionally, reducing their fight-or-flight and stress levels.