Common Channels of Communication in the Workplace

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Explain the information richness of various channels.

- Know when to use written versus verbal communication.

- Understand the direction of communication in organizations.

Now that we’ve built a foundation for organizational communication, let’s review our learning before moving on to other aspects of workplace communication. Remember that the channel, or medium, used to communicate a message affects how accurately the message will be received. Verbal, written, and nonverbal communications have different strengths and weaknesses. In the workplace, the decision to communicate verbally or in written form can be a powerful one. In addition, a competent manager is aware of the nonverbal messages conveyed by both types of communication, as noted earlier; only 7% of verbal communication comes from the words themselves.

Information Richness

Channels vary in their information richness. Information-rich channels convey more nonverbal information. As you may be able to guess from our earlier discussion of verbal and written communications, verbal communications are richer than written ones. Research indicates that effective managers utilize more information-rich communication channels than their less effective counterparts (Allen & Griffeth, 1997; Fulk & Boyd, 1991; Yates & Orlikowski, 1992). Table 4.1 illustrates the information richness of different information channels.

Table 5.1.1 Guide for When to Use Written Versus Verbal Communication

Like face-to-face and telephone conversations, videoconferencing has high information richness because communicators can see or hear beyond just the words—they can see body language or hear the tone of their voice. Handheld devices, blogs, written letters, and memos offer medium-rich channels because they convey words and pictures/photos. Formal written documents, such as legal documents, and spreadsheets, such as the division’s budget, represent the least richness because the format is often rigid and standardized. As a result, nuance is lost. When communicating verbally or in writing, ask yourself: Do I want to convey facts or feelings? Verbal communication is a better way to express emotions, while written communication conveys facts more effectively.

The Manager’s Speech

Picture a manager making a speech to a team of 20 employees. The manager is speaking at a normal pace. The employees appear interested. But how much information is being transmitted? Not as much as the speaker believes! Humans listen much faster than they speak.

Reflect on the section on listening and the effort required for the five stages of listening. Now, consider that the average public speaker communicates at a speed of about 125 words a minute. And that pace sounds acceptable to the audience. (In fact, anything faster than that probably would sound weird. To put that figure in perspective, someone having an excited conversation speaks at about 150 words a minute.)

Based on these numbers, we could assume the employees have enough time to take in each word the manager delivers. And that’s the problem. The average person in the audience can hear 400–500 words a minute (Lee & Hatesohl, 2008). The audience has more than enough time to listen to. As a result, they will each be processing many thoughts on totally different subjects while the manager is speaking. This example demonstrates that oral communication is an inherently flawed medium for conveying specific facts. Listeners’ minds wander! It’s nothing personal—in fact, it’s physical. Once we understand this fact in business, we can make more intelligent communication choices based on the information we want to convey.

The key to effective communication is to match the communication channel with the goal of the communication (Barry & Fulmer, 2004). For example, written media may be a better choice when the communicator wants a record of the content, has less urgency for a response, is physically separated from the receiver, doesn’t require a lot of feedback, or the message is complicated and may take some time to understand. Oral communication is more effective when conveying a sensitive or emotional message, requires immediate feedback, and does not necessitate a permanent conversation record. Table 5.2.2 provides a guide for deciding when to use written versus verbal communication.

Table 5.2.2 Guide for When to Use Written Versus Verbal Communication

Business Use of E-Mail

The growth of e-mail has been spectacular, but it has also created challenges in managing information and an ever-increasing speed of doing business. Learning to be more effective in your email communications is an important skill. To learn more, check out the business e-mail dos and don’ts.

Business E-Mail Do’s and Don’ts

- DON’T send or forward chain e-mails.

- DON’T put anything in an e-mail you don’t want the world to see.

- DON’T write a message in capital letters—this is the equivalent of SHOUTING.

- DON’T routinely “cc” everyone all the time. Reducing inbox clutter is a great way to increase communication.

- DON’T hit Send until you spell-check your e-mail.

- DO use a subject line that summarizes your message, adjusting it as the message changes over time.

- DO make your request in the first line of your e-mail. (If that’s all you need to say, stop there!)

- DO end your e-mail with a brief sign-off, “Thank you,” followed by your name and contact information.

- DO think of a work email as a binding communication.

- DO let others know if you’ve received an e-mail in error.

Source: Adapted from information in Leland, K., & Bailey, K. (2000). Customer service for dummies. Wiley; Information Technology Services. (1997). Top 10 email dos and top 10 email don’ts. University of Illinois at Chicago Medical Center. http://www.uic.edu/hsc/uicmc/its/customers/email-tips.htm; Kawasaki, G. (2006, February 3). The effective emailer. How to Change the World. http://blog.guykawasaki.com/2006/02/the_effective_e.html.

An important, although often ignored, rule when communicating emotional information is that e-mail’s lack of richness can be your loss. As we saw in the chart above, e-mail is a medium-rich channel. It can convey facts quickly. However, regarding emotion, e-mail’s flaws make it far less desirable than oral communication; 55% of nonverbal cues that make a conversation comprehensible to a listener are missing. In a recent study, researchers note that email readers don’t pick up on sarcasm and other tonal aspects of writing as much as the writer believes they will (Kruger, 2005). The sender may think they have included these emotional signifiers in their message. But with words alone, those signifiers are not there. This gap between the form and content of e-mail inspired the rise of emoticons, symbols that offer clues to the emotional side of the words in each Message. Generally speaking, however, emoticons are not considered professional in business communication.

You may feel uncomfortable conveying an emotionally charged message verbally, especially when it contains unwelcome news. Sending an e-mail to your staff that there will be no bonuses this year may seem easier than breaking the evil news face-to-face, but that doesn’t mean that e-mail is an effective or appropriate way to deliver this kind of news. When the message is emotional, the sender should use verbal communication to convey it effectively. Indeed, a good rule of thumb is that the more emotionally laden messages require more thought in the channel choice and how they are communicated.

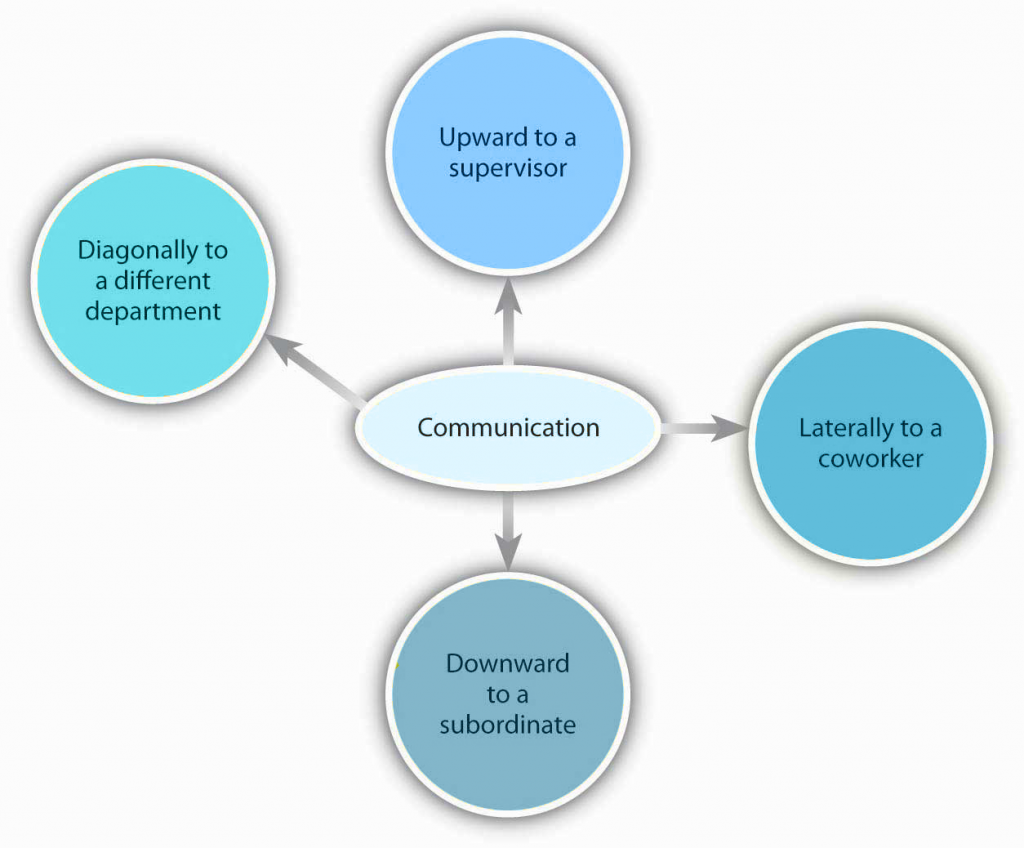

Direction of Communication Within Organizations

As we learned in our previous chapters, information can move horizontally, from a Sender to a Receiver, as we’ve seen. It can also move vertically, down from top management or up from the front line. Information can also move diagonally between and among levels of an organization, such as a message from a customer service representative up to a manager in the manufacturing department, or a message from the chief financial officer sent down to all department heads.

There is a chance for these arrows to go awry, of course. As Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (2004), author of best-selling books such as Flow, has noted, “In large organizations, the dilution of information as it passes up and down the hierarchy, and horizontally across departments, can undermine the effort to focus on common goals” (p. 75). Managers need to remember this when they make organizational design decisions as part of the organizing function. The sender’s organizational status can affect the receiver’s attentiveness to the message. For example, consider a senior manager sending a memo to a production supervisor. The supervisor, who has a lower status within the organization, will likely pay close attention to the message. However, the same information conveyed in the opposite direction might not get the attention it deserves. The senior manager’s perception of priorities and urgencies would filter the message.

External Communications

External communications deliver specific business messages to individuals outside an organization. They may announce changes in staff or strategy, earnings, and more. The goal of external communication is to create shared understanding. Examples of external communications include press releases, advertisements, web pages, and customer communications, such as catalogs.

Key Takeaway

- Understanding the channel richness and the appropriate way to communicate is crucial to succeeding in workplace communication.

References

This section is adapted from:

Principles of Management for Leadership Communication by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Allen, D. G., & Griffeth, R. W. (1997). Vertical and lateral information processing. Human Relations, 50(10), 1239-1260.

Barry, B., & Fulmer, I. S. (2004). The medium and the message: The adaptive use of communication media in dyadic influence. Academy of Management Review, 29, 272–292.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2004). Good business: Leadership, flow, and the making of meaning. Penguin.

Fulk, J., & Boyd, B. (1991). Emerging theories of communication in organizations. Journal of Management, 17, 407–446.

Kruger, J. (2005). Egocentrism over email: Can we communicate as well as we think? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 925–936.

Lee, D., & Hatesohl, D. (2008). Listening: Our most used communication skill. University of Missouri. Retrieved July 2, 2008, from http://extension.missouri.edu/explore/comm/cm0150.htm.

Yates, J., & Orlikowski, W. J. (1992). Genres of organizational communication: A structurational approach to studying communication and media. Academy of Management Review, 17, 299–326.

Attribution

Psychology, Communication, and the Canadian Workplace Copyright © 2022 by Laura Westmaas, BA, MSc is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Figure 1 Adapted from Principles of Management for Leadership Communication by University of Minnesota information . CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Color altered from original.

Table 1 & 2 Adapted from Principles of Management for Leadership Communication: Leadership Communication Edition, University of Arkansas. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Converted from original to a table.

the capacity of a communication method to convey detailed information and context.

specific business messages delivered to individuals outside an organization.