Speech Structure

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Create a preparation outline and a speaking outline for an extemporaneous speech.

- Use keywords from an outline to develop a speaking outline.

As you saw in the last chapter, an extemporaneous style of speech delivery is an effective way to keep an audience energized about and engaged with a topic. Many individuals may feel a bit uncomfortable with this idea if they are used to using a manuscript or memorized style. This chapter will show you how to outline a speech and give you several elements you can use while designing it.

Outlining Your Speech

An outline provides a visual structure where you can compile information into a well-organized document. The amount of information you include will depend on your needs. For an organizational communication course, use a preparation outline, which is a comprehensive form of outline that includes all of the information in your speech. If someone were to read your preparation outline, it should provide enough depth to give a general idea of what will be accomplished.

Generally, we recommend starting from this outline format:

|

Sample Speech Outline |

|

I. Introduction a. Attention Getter / Hook |

II. Main body

|

| III. Conclusion

a. Summary: Review of Main Points |

You should think of the outline as the blueprint for your speech. It is not the speech—that is what comes out of your mouth in front of the audience. The outline helps you prepare and, as such, is a living document that you can adjust, add to, and delete. A good way to begin is by adding information right away. During an extemporaneous speech, you will not have the whole document during your speech. Reducing words and phrases from your outline until you have a short speaking outline will keep you focused on delivering an effective speech to your audience. Your speaking outline might be a 3×5 card or a straightforward page using a large font that you can quickly glance over. A speaking outline is a keyword outline used to deliver an extemporaneous speech. The notes you use to speak can aid or hinder an effective delivery.

A keyword outline allows greater embodiment and engagement with the audience. As you practice an extemporaneous speech, summarize the complete preparation outline into more usable notes. In those notes, create a set of abbreviated notes for the actual delivery. The more materials you take to speak, the more you will be tempted to look at them rather than maintain eye contact with the audience, which reduces your overall engagement. Your speaking notes should be in far fewer words than the preparation, arranged in key phrases, and readable for you. Your speaking outline should provide cues to yourself to “slow down,” “pause,” or “change slide.” Our biggest suggestion is to make the notes workable for you. More information on structuring your cue card is included in the next section.

Using Cue Cards

An extemporaneous speech is a presentation that is delivered without careful planning or preparation. A tool that can help you in your speech is to use a speaking outline effectively. A 3×5 or one-page speaking outline is meant to help prompt you as you give your speech and to keep you on track. It is not meant to be a transcript of your speech.

Exercise: Evaluate Cue Cards

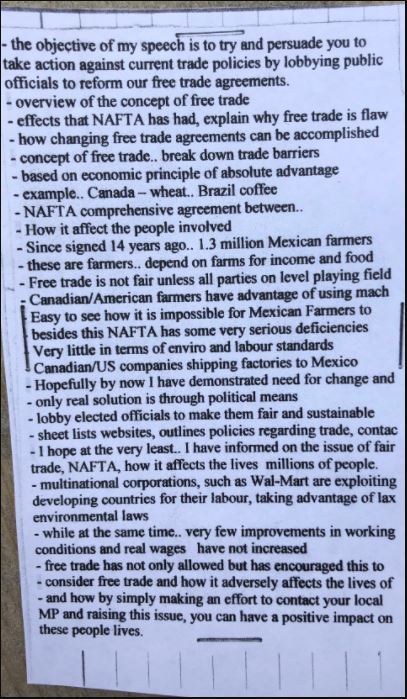

Below are images of three cue cards. Look at Image #1. Do you think this person’s speech was successful according to the constraints of an extemporaneous speech? Why or why not?

Image #1 is an example of what not to do when using a cue card. Remember that your card is a tool to consult while you speak. You do not need to write everything you would like to say on it.

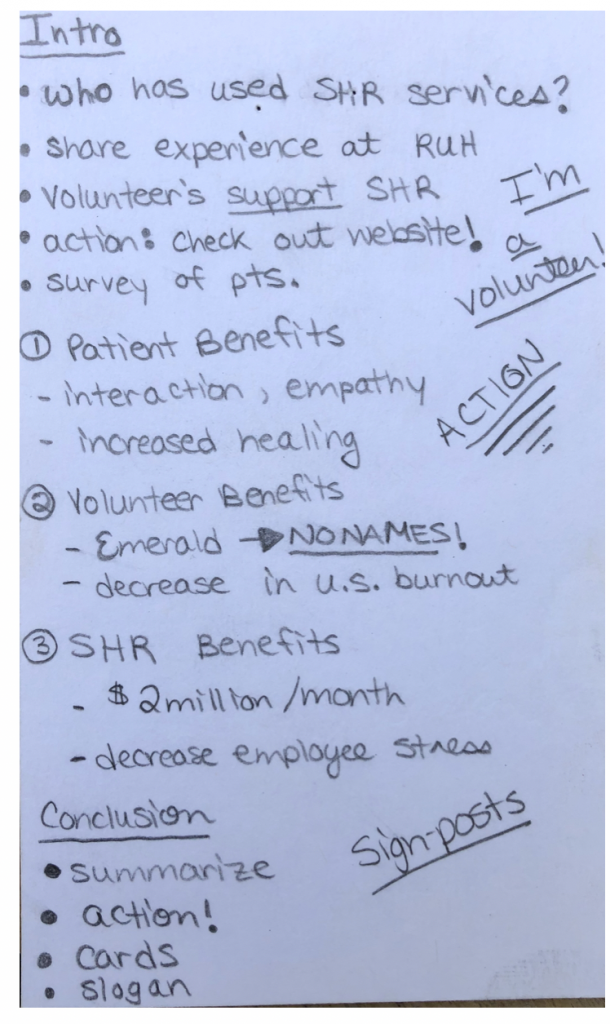

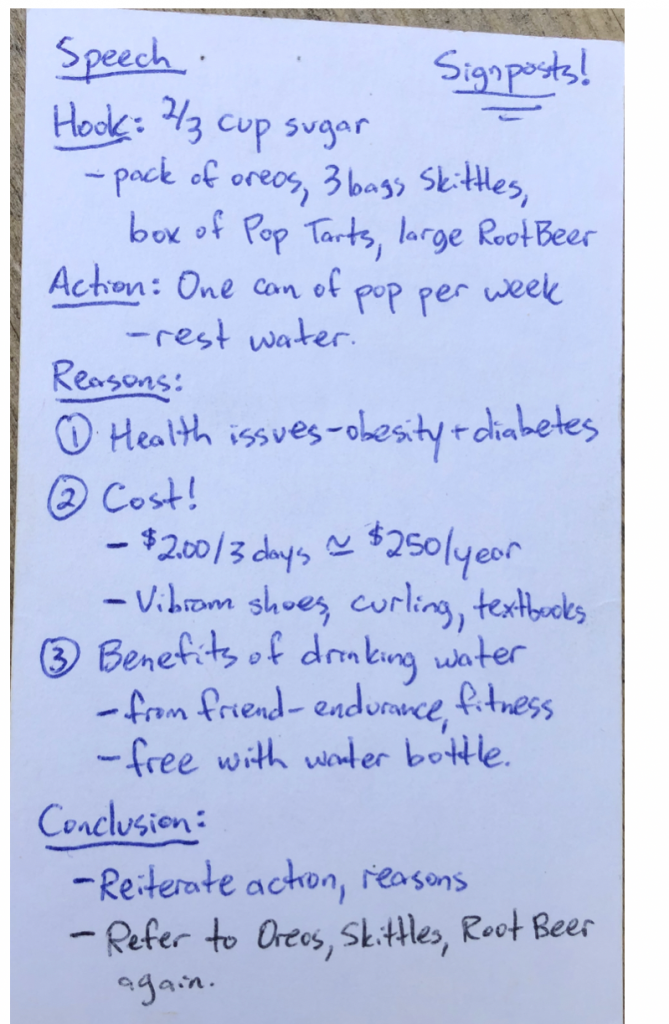

Now, look at two more cue cards (Images #2 and #3). What is it that makes these two cards better? How are they different from Image #1?

Your card is intended to be recognized by you (the speaker) and you alone, so you can use abbreviations (similar to the ‘SHR’ used in Image #2 above) or have shorthand notes that will help jog your memory. Recognize that you probably will NOT need to write as much on your cue card as you may think you need to. As you practice, ensure that you use the same card.

Setting Up Your Speech

Introductions and conclusions frame the speech, clearly defining its beginning and end. They help the audience anticipate what is to come in the speech and then mentally prepare for the conclusion. In doing this, introductions and conclusions provide a “preview/review” of your speech to reiterate what you are talking about to your audience. Because speeches are auditory and live, audiences must remember what you are saying. The general rule is that the introduction and conclusion should each be about 10% of your total speech, leaving 80% for the body section. It can be tempting to have longer introductions, but that often leaves less time to introduce key research and warrant your ideas through the main points. The introduction and conclusion should be about 30 seconds in a five-minute speech.

Structuring the Introduction

|

Common Errors to Avoid in Introductions

|

|

With that in mind, incorporate the following five basic elements into your introduction and speech outline.

Element 1: Get the Audience’s Attention—the Hook

The first central purpose of an introduction is to gain your audience’s attention and make them interested in what you have to say. The first words of a speech should be something that will perk up the audience’s ears. Starting a speech with “Hey everybody, I’m going to talk to you today about soccer” does not try to engage the audience members who don’t care about soccer. The key to creating interest is selecting an appropriate and relevant option for your audience. You will also want to choose an attention-getting device that is suitable for your speech topic. Ideally, your attention-getting device should be appropriately connected to your speech. Below are several options for crafting an attention-getting headline.

Anecdotes and Narratives

An anecdote is a brief account or story of an interesting or humorous event. Notice the emphasis here is on the word “brief.” An example of an anecdote used in a speech about the pervasiveness of technology might look something like this:

Notice that the anecdote is short and makes a clear point. The speaker can then explain how technology controls our lives. Another option here is a personal story. You may start your speech with a story about yourself relevant to your topic. Some of the most effective speeches draw on personal knowledge and experience. Suppose you are an expert or have firsthand experience related to your topic. In that case, sharing this information with the audience is a great way to show credibility during your attention-getter.

Startling Statement/Statistic/Fact

Another way to start your speech is to surprise your audience with startling information about your topic. Often, startling statements come in the form of statistics and strange facts. A good startling statistic aims to surprise and engage the audience in your topic. For example, if you’re giving a speech about oil conservation, you could start by saying:

You could start a speech on the psychology of dreams by noting:

On the other hand, a strange fact is a statement that does not involve numbers but is equally surprising to most audiences. For example, you could start a speech on the gambling industry by saying:

Although startling statements are fun, it is vital to use them ethically. First, ensure that your startling statement is factually accurate. Second, ensure that your startling statement is relevant to your speech and not merely included for shock value.

A Rhetorical Question

A rhetorical question is a question to which no actual reply is expected. For example, a speaker talking about the history of Mother’s Day could start by asking the audience:

In this case, the speaker does not expect the audience to shout out an answer but rather to consider the questions as the speech proceeds.

Quotation

Another way to capture your listeners’ attention is to use another person’s words that relate directly to your topic. Maybe you’ve found an extraordinary quotation in one of the articles or books you read while researching your speech. If not, you can use several Internet or library sources that compile valid quotations from noted individuals. Quotations are a great way to start a speech, so let’s look at an example that could be used during the opening of a commencement address:

Element 2: Establish or Enhance Your Credibility

Whether you inform, persuade, or entertain an audience, they expect you to know what you’re talking about. The second element is to let your audience know that you are a knowledgeable and credible source for this information. In other words, you must establish your ethos. To do this, you will need to explain how you acquired your knowledge about your topic. For some, this will be straightforward. If you inform your audience about a topic you’ve researched or experienced for years, that makes you a reasonably credible source. You probably know what you are talking about. Let the audience know! For example:

However, you may be speaking on a subject with which you have no history of credibility. You can do that if you are curious about when streetlights were installed at intersections and why they are red, yellow, and green. However, you will still need to provide your audience with a reason to trust your knowledge. Conducting research using reliable sources demonstrates that you are at least more knowledgeable on the subject and respect the audience enough to ensure they receive accurate, ethical, and balanced information on a topic.

Element 3: Establish Relevance through Rapport

Next, you must establish rapport with your audience. Rapport is a relationship or connection you make with your audience, similar to incorporating pathos appeals in your speech. In everyday life, two people have a rapport when they get along well and are good friends. In your introduction, explain to your audience why you are providing them with this information and why it is essential or relevant to them. You will establish a connection through this shared information and explain to them how it will benefit them.

Element 4: State your Thesis

After you get the audience’s attention, you must reveal the purpose of your speech to your audience. Have you ever sat through a speech wondering what the basic point was? Have you ever left a speech and had no idea what the speaker was talking about? An introduction should clearly define the topic, purpose, and central idea. Remember rhetorical exigence from previous chapters? This is essentially what your thesis is doing: you are addressing a problem that your audience has and showing them you have the answer. When stating your topic in the introduction, be clear and explicit about it. Spell it out for them if necessary. If an audience cannot remember all your information, they should at least be able to walk away knowing the purpose of your presentation. Make sure your logos appeals are solid.

Element 5: Preview Your Main Points—the Survey

Like previewing your topic, previewing your main points helps your audience know what to expect throughout your speech. This part of the speech could be called the survey or preview. Your preview of the main points should be straightforward to follow so that there is no question in your audience’s minds about what they are. Long, complicated, or verbose main points can get confusing. Be succinct and straightforward in your survey:

From that, there is little question about what specific aspects of Lincoln’s life the speech will cover. However, if you want to be extra sure they get it, you can always enumerate them:

These five elements prepare your audience for the bulk of the speech (i.e., the body section) by letting them know what they can expect, why they should listen, and why they can trust you. Having all five elements sets your speech off on much more solid ground than you would without them.

The Body: Connecting Your Points Using Signposts

At this point, you may realize that preparing for public speaking does not always follow a completely linear process. In writing your speech, you might begin outlining with one organizational pattern in mind, only to recraft the main points into a new pattern after more research has been conducted. These are all okay options. Wherever your process takes you, however, you will need to make sure that each section of your speech outline uses connective statements or signposts. A connective statement, also known as a “signpost,” is a broad term encompassing several types of statements or phrases. They are generally designed to help “connect” parts of your speech to make it easier for audience members to follow. Connectives are tools for helping the audience listen, retain information, and follow your structure.

Signposts perform several functions:

- Remind the audience of what has come before.

- Remind the audience of the central focus or purpose of the speech.

- Forecast what is coming next.

- Help the audience understand the speech’s context—where are we? (This is especially useful for a longer speech of twenty minutes or so.)

- Explain the logical connection between the previous main idea(s) and the next one, or the previous subpoints and the next one.

- Explain your mental processes in arranging the material as you have.

- Keep the audience’s attention through repetition and a sense of movement.

Signposts can include internal summaries, numbering, or internal previews. Each of these terms helps connect the main ideas of your speech to the audience, but they have different emphases and are helpful for various types of speeches.

Types of connectives and examples

Signposts emphasize the physical movement through the speech content and let the audience know precisely where they are. Signposting can be as simple as “First,” “Next,” or “Lastly,” or using numbers such as “First,” “Second,” Third,” and “Fourth.” Signposts can also be lengthier, but in general, signposting is meant to be a brief way to let your audience know where they are in the speech. It may help to think of these, like the mile markers you see along interstates that tell you where you are, or signs letting you know how many more miles you will have until you reach your destination.

Internal summaries emphasize what has come before and remind the audience of what has been covered.

Internal previews let your audience know what will happen next in the speech and what to expect regarding the content of your speech.

Transitions serve as bridges between seemingly disconnected (but related) material, most commonly between your main points. At a bare minimum, your transition is saying,

Connectives are essential for helping the audience understand a) where you’re going, b) where you are, and c) where you’ve been. We recommend labeling them in your outline to ensure they’re integrated and transparent.

Wrapping Up: The Summary

Like the introduction, the conclusion must incorporate three elements to be as strong as possible.

|

Common Errors to Avoid in Conclusions

|

|

Given the nature of these elements and what they do, these should generally be incorporated into your conclusion in the order presented below.

Element 1: Review Main Points

Remember, introductions preview your main points; the conclusion provides a review. One of the most significant differences between written and oral communication is the necessity of repetition in oral communication. Your audience only has one opportunity to catch and remember the points you are trying to get across in your speech, so the review assists in repeating key ideas that support your thesis statement. You want to avoid introducing new material or ideas because you are trying to reinforce the audience’s understanding of your main points. For example, if you said, “There are several other issues related to this topic, such as…, but I don’t have time for them,” that would confuse the audience and perhaps make them wonder why you did not address those in the body section. The hardcore facts and content are in the body.

Element 2: Restate the Thesis

Restate your thesis because this is the main argument you leave the audience with. While this may come before or after reviewing your main points, it’s important because it often directs the audience and reminds them of the purpose for which they’re present. Concluding without reiterating your thesis statement requires the audience to recall an idea from the introduction, which can feel like a distant memory.

Element 3: Clincher

The third element of your conclusion is the clincher, or something memorable with which to conclude your speech. The clincher is sometimes referred to as a concluding thought. These are the last words you will say in your speech, so you must make them count. In many ways, the clincher is the inverse of the attention-getter. You want to start the speech off with something substantial, and you want to end the speech with something substantial. To that end, you can make your clincher strong and memorable in several ways, similar to what we discussed above with attention-getters.

| Strategies for Effective Concluding Thoughts | |

| Conclude with a Challenge | A challenge is a call to engage in some activity that requires |

| Conclude with a Quotation | Select a quotation that’s related to your topic |

| Visualize the Future | Help your audience imagine the future you believe can occur. |

| Conclude by Inspiration | Use inspiration to evoke a specific emotional response in someone. |

| Conclude with a Question | Pose a rhetorical question that prompts the audience to consider an idea. |

| Refer to the Introduction | Come full circle by referencing an idea, statistic, or insight from the attention-getter. |

| Conclude with a Story | Select a brief story aimed at a strong emotional appeal |

For the conclusion, make sure your purpose—informative, persuasive, entertaining—is honored.

Key Takeaways

- The organization and outlining of your speech may not be the most interesting part to think about, but without it, great ideas will seem jumbled and confusing to your audience. To help you prepare for your presentation, you will need to create a preparation outline.

- Use keywords from your speaking outline to create a cue card. This piece of paper will help guide you through your speech; however, it should serve more as a reminder of your key points than as a resource you continually refer to.

- Your introduction is what captures your audience’s interest in your topic. You can get their attention with a hook, establish credibility, establish rapport, state your thesis, and survey your main points.

- In your body, good signposts or connective statements will ensure your audience can follow you and understand the logical connections you make between your main ideas, introduction, and conclusion.

- The conclusion provides a summary of the points you have just discussed. Ideally, the conclusion should remind your audience of what you discussed and why it matters to them. You can do this in your summary by reviewing the main ideas, restating the thesis, and ending the speech in a memorable way with a clincher.

Attribution

This chapter is adapted from “Speak Out, Call In: Public Speaking as Advocacy” by Meggie Mapes (on Pressbooks). It is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

a speech delivery method where the presentation is carefully planned and rehearsed, but spoken in a conversational manner using brief notes

a speech delivery method where a message is read word-for-word off a written page or autocue device

a speech delivery method where a message is presented after being committed to memory by the speaker

a visual structure where you can compile information into a well-organized document

a comprehensive form of outline that includes all of the information in your speech

a keyword outline used to deliver an extemporaneous speech

something that makes it difficult for your message to be received, such as beliefs, facts, interests, and motives. These can from both the rhetor and the audience

a rhetorical appeal that addresses the values of an audience as well as establishes authorial credibility/character

a rhetorical appeal that tries to tap into the audience's emotions to get them to agree with a claim

a "problem" that can be affected by human activity

a rhetorical appeal that requires the use of logic, careful structure, and objective evidence to appeal to the audience

several types of statements or phrases that are designed to connect part of your speech to make it easier for audience members to follow

emphasize what has come before and remind the audience of what has been covered.

let your audience know what will happen next in the speech and what to expect regarding the content of your speech.

serve as bridges between seemingly disconnected (but related) material, most commonly between your main points.