The Basic Elements of a Sentence

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Recognize the difference between a clause and a phrase.

- Distinguish between an independent clause and a dependent clause.

- Identify and explain the four sentence structures (simple, compound, complex, compound-complex).

Unsurprisingly, you are required to submit written assignments for this course. Your level of comfort in this area will differ from that of other students, but like all skills, writing is improved through practice. We all have strengths in writing, and we all have areas we can improve.

We will start small now and focus on sentence-level issues that can harm your writing. This way, we have a common language as we discuss this topic. After that, you’ll have a chance to pick a common writing issue that is relevant to you.

Let’s start by reviewing the basic grammatical terms you need to know for this section.

Exercise #1: Grammar Vocabulary Self-Assessment

Below, you will see some flash cards with grammatical terms. These are all terms that we will mention throughout this technical writing section. Try to predict what you think these words mean. If you can’t define the word, can you come up with an example? If the definitions don’t make sense yet, that’s okay! We’ll go into these things later. This assessment is just for you to test your knowledge.

Clauses and Phrases

When building anything, be it a car, a house, or even a sentence, it is essential to be familiar with the tools you are using. For this course, grammatical elements are the main “tools” used when building sentences and longer written works such as reports. Thus, it is critical to understand grammatical terminology to construct effective sentences. If you want to review some essential parts of speech (nouns, pronouns, articles, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, etc), see the Parts of Speech Overview at the Purdue OWL website. Now, let’s get into it!

The two essential parts of a sentence are the subject and the verb. The subject refers to the topic being discussed, while the verb conveys the action or state of being expressed in the sentence. When you combine these two elements, you get a clause. All clauses must contain both a subject and a verb.

Here are two simple examples of a clause.

(2) I eat food.

Some phrases lack a subject, a verb, or both, so they need to relate to or modify other parts of the sentence. Don’t worry too much about phrases though. We are going to focus on clauses here.

Independent or main clauses can stand independently and convey an idea. Let’s look at some examples.

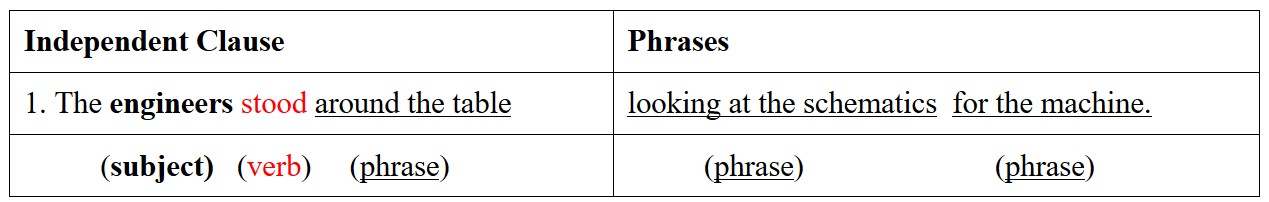

Here is a sentence:

Can you identify the subject, verb, clause, and phrase in that sentence? If not, that’s okay.

Here’s a breakdown of the different parts of the sentence.

Notice the independent clause [The engineers stood around the table] is a complete idea. The independent clause would work as a complete sentence if we took at the phrase. The phrase [looking at schematics for the machine] is not. It has a verb [looking], but not a subject, so it isn’t a clause. It could not be a complete sentence on its own.

Dependent clauses rely on another part of the sentence for meaning and can’t stand alone.

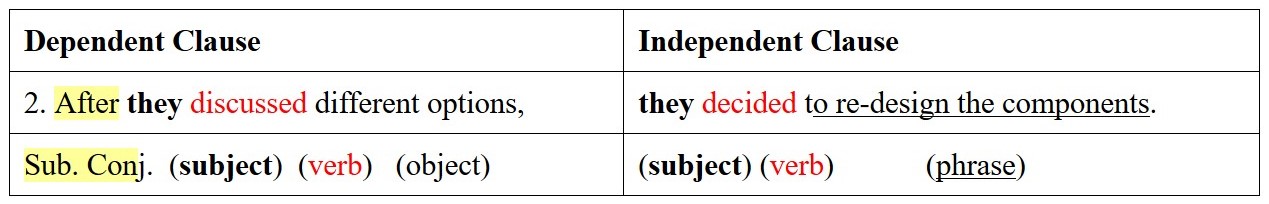

Here’s an example:

Can you identify the different parts we have discussed so far? Below is a breakdown of the sentence.

Sentence 2 has one dependent clause and one independent clause, each with its subject-verb combination [“they discussed” and “they decided”]. The two clauses are joined by the subordinate conjunction, “after,” which makes the first clause subordinate to (or dependent upon) the second one.

Identifying the critical parts of the sentence will help you design sentences with a clear and compelling subject-verb relationship.

If you need more guidance on clauses, please watch one or both of the videos below. The first video is humorous, while the second is more formal.

Link to Original Video: https://tinyurl.com/holidayclause

Link to Original Video: https://tinyurl.com/indepclauses

Exercise #2: Identify the Clause

In this activity, you will identify all the words in a sentence’s independent or dependent clauses. You must click on all the words in that clause to get the points.

For example, if you are supposed to identify an independent clause, and your sentence is

I will go to work after I eat breakfast.

You would click on “I,” “will,” “go,” “to,” and “work.”

If you are supposed to identify a dependent clause for the same sentence, you would click on “after” “I” “eat” and “breakfast”.

Sentence Structures

Sentence structures are how we combine independent clauses, dependent clauses, and phrases to create complete ideas in our writing. There are four main types of sentence structures: simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex. In the examples above, Sentence 1 is simple, while Sentence 2 is complex.

We will go over each sentence structure now.

SIMPLE SENTENCES have one main clause clause and any number of phrases. Below is the formula for a simple sentence.

The following are all examples of simple sentences:

- A simple sentence can be very effective.

- It makes one direct point.

- It is good for creating emphasis and clarity.

- Too many in a row can sound repetitive and choppy.

- Varied sentence structure sounds more natural.

Can you identify the subject, verb, and phrases (if any) in the above sentences?

COMPOUND SENTENCES have two or more main clauses joined by coordinating conjunctions (CC) such as and, but, for, yet, nor, or, so. A common acronym for remembering all of the conjunctions is FANBOYS. You can also connect them using punctuation, such as a semicolon or a colon. By coordinating the ideas, you give them roughly equal weight and importance.

Please note that these coordinating conjunctions are different from subordinate conjunctions, which show a generally unequal relationship between the clauses.

Below is the formula for a compound sentence:

- A compound sentence coordinates two ideas, each given roughly equal weight.

- The two ideas are closely related, so you don’t want to separate them with a period.

- The two clauses are part of the same idea, so they should be part of the same sentence.

- The two clauses may express a parallel idea, and they might also have a parallel structure.

- You must remember to include the coordinating conjunction, or you may commit a comma splice.

In formal writing, avoid beginning a sentence with a coordinating conjunction.

COMPLEX SENTENCES express complex and usually unequal relationships between ideas. One idea is “subordinated” to the main idea by using a subordinate conjunction (like “while” or “although”). One idea is “dependent” upon the other one for logic and completeness. Complex sentences include one main clause and at least one dependent clause (see Example 2 above). Often, it is stylistically effective to begin your sentence with the dependent clause and place the main clause at the end for emphasis.

The following are all examples of complex sentences. Subordinate conjunctions are in bold.

- When you make a complex sentence, you subordinate one idea to another.

- If you place the subordinate clause first, you emphasize the main clause at the end.

- Even though many students try to use them that way.

- xNOTE: This last bullet is a sentence fragment, not a subordinate clause. Subordinate clauses cannot stand on their own.

Check out this link for a list of subordinate conjunctions if you want more examples.

COMPOUND-COMPLEX SENTENCES have at least two independent clauses and at least one dependent clause. Because a compound-complex sentence is usually quite long, you must be careful that it makes sense; it is easy for the reader to get lost in a long sentence.

Given the complex nature of the structure, let’s look at a few examples and break them down into their parts:

Independent Clause #1: Alphonse doesn’t like action movies.

Dependent Clause: because they are so loud

Independent Clause #2: he doesn’t watch them.

Dependent Clause: Although it will be close

Independent Clause #1: I think we will meet the deadline

Independent Clause #2: We will complete the project.

While our supervisor can be a bit of a jerk sometimes, she genuinely cares about the work and wants to see us succeed.

Dependent Clause: While our supervisor can be a bit of a jerk at times

Independent Clause #1: She genuinely cares about the work

Independent Clause #2: She wants to see us succeed

EXERCISE #3 Identifying Sentence Types

Read the sentences below and identify which sentence structure is being used.

EXERCISE #4: Combining sentences

Below are two sentences separated by a line ( | ). Combine the pair of sentences to make one idea subordinate to the other. You can do this by writing them down or thinking them in your mind. When you have an answer, click on the sentences for two possible answers.

Notice the impression you convey by how you subordinate one idea to another. If your combined sentence were a topic sentence for a paragraph, what idea would the reader expect that paragraph to emphasize?

Now that you know different sentence structures, let’s focus on specific issues that can damage your writing. Below are links to other chapters, each with its particular writing focus. Since everyone’s needs will differ, please focus on one chapter you think you need the most help with. Each section will have activities for you to do to check your understanding of the content.

If you’re unsure which to choose, ask yourself the questions below. If you don’t know the answer, click the link to be taken to the appropriate section.

- Are your sentences often too short and do not convey complete ideas? (Sentence Fragments)

- Do you write in long, confusing sentences and don’t know how to break them up? (Run-On Sentences)

- When is it appropriate to use the passive voice? Is a nominalization a good thing? (Verb Tense)

- Do you know how to use a semicolon or colon? (Punctuation)

- Have you ever been told that your writing needs to be trimmed down? (Eliminating Wordiness)

Key Takeaways

- A sentence must have a subject and a verb to form a complete idea.

- A clause has both a subject and a verb. There are two types of clauses: an independent clause (which can stand alone) and a dependent clause (which can not stand alone).

- Using a variety of sentence types and using these types strategically to convey your ideas will strengthen your style. Keep the following in mind:

- Simple sentences are great for emphasis. They make great topic sentences.

- Compound sentences balance ideas; they are great for conveying the equal importance of related ideas.

- When used effectively, complex sentences show complicated relationships between ideas by subordinating one idea to another.

- Compound-complex sentences can add complexity to your writing, but you need to ensure that the writing doesn’t lose the reader.

- Ultimately, using a combination of these structures will make your writing stronger.

References

Purdue Writing Lab. (n.d.). Parts of speech overview. https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/mechanics/parts_of_speech_overview.html

Attributions

This chapter is adapted from “Technical Writing Essentials” by Suzan Last (on BCcampus). It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

the topic being discussed in a clause or sentence

a word that conveys the action or state of being in a sentence

when a subject and verb are combined in a sentence. There are two types: independent clause and dependent clause.

Chapter Preview

- What is a Group?

a group of words that are missing a subject, a verb, or both

a word that connects a dependent clause to an independent clause. It shows a cause-and-effect relationship or a shift in time and place between the two clauses

a clause that can stand on it's own because it conveys a complete idea.

a clause that relies on another part of the sentence for meaning because it cannot stand on it's own

a word that joins two clauses. These include words like and, but, for, yet, nor, or, so